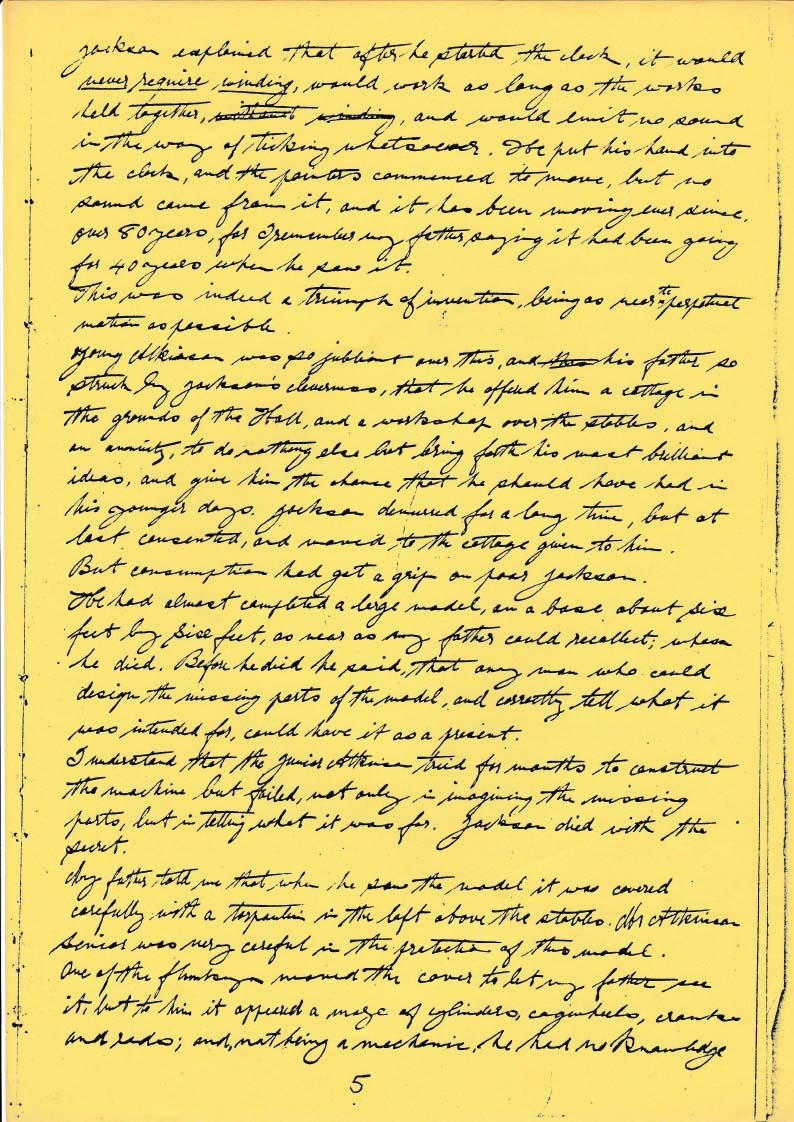

Jackson explained that after he started the clock, it would never require winding, would work as long as the works held together without winding, and would emit no sound in the way of ticking whatsoever. He put his hand into

the clock

and the pointers commenced to move, but no sound came from it, and it has been moving ever since, over 80 years, for I remember my father saying it had been going for 40 years when he saw it.

This was indeed a triumph of invention, being as near to perpetual motion as feasible.

Young Atkinson was so jubilant over this, and his father so struck by Jackson’s cleverness, that he offered him a cottage in the grounds of the Hall, and a workshop over the stables, and an annuity, to do nothing else but bring forth his most brilliant ideas, and give him the chance that he should have had in his younger days. Jackson demurred for a long time, but at last consented, and moved to the cottage given to him. But consumption had got a grip on poor Jackson. He had almost completed a large model, on a base about six feet by six feet, as near as my father could recollect; when he died. Before he died he said that any man who could design the missing parts of the model, and correctly tell what it was intended for, could have it for a present.

I understand that the junior Atkinson tried for months to construct the machine but failed, not only in imagining the missing parts, but in telling what it was for. Jackson died with the secret.

My father told me that when he saw the model it was covered carefully with a tarpaulin in the loft above the stables. Mr Atkinson Senior was very careful in the protection of this model. One of the flunkeys moved the cover to let my father see it, but to him it appeared a maze of cylinders, cogwheels, cranks and rods; and, not being a mechanic, he had no knowledge