Pitmen

If the movement around the pits of the north east which his grandparents, parents and then WILLIAM himself made during the eighty years from 1815 to 1895 are plotted on relevant maps, it can be seen that the family moved from Wylam and Tow Law in the west, to Whitburn and Blyth in the east; from Coundon in the south to Amble in the north. In other words they traversed almost the whole of the northern coalfield!

WILLIAM’S family can truly claim to be Northumberland and Durham miners.

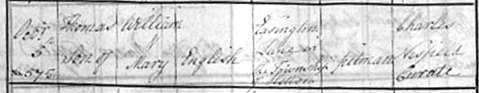

Two of WILLIAM’S great grandfathers, William English (b 1795 Houghton le Spring, baptised in Auckland St Andrew), and John Lawson (bc 1781, Houghton le Spring) describe themselves at the baptism of their respective children, as pitmen.

On 15 October 1815 John Lawson gives his occupation as pitman and signs the register at the baptism of both his daughters, (Helen born 16th February 1813 and Mary, born 29 March 1815) at Fatfield

On 5 October 1828 William English gives his occupation as pitman at the baptism of his son Thomas, WILLIAM’S grandfather, at Houghton le Spring.

The general consensus was that pitmen were bred as well as trained. The quotes below demonstrate this. This was the world WILLIAM’S great grandfathers were born into.

| The word pitman carried with it meanings of social bearing: other men were colliers compared to pitmen and others again were labourers compared with colliers. | In 1809 there were 1,980 bound hewers on Tyneside ‘a corps small enough to be known by name, ability, and temperament by the agents who employed them’ |

Changing attitudes and status

By 1832 when their sons Thomas English, (b 1828, Hetton le Hole) and William Lawson, (b 1827 Houghton-le-Spring), William’s grandfathers, were born, the pitman’s status was changing. In 1831 a correspondent to a local newspaper wrote:

| Hitherto the pitwork has been a monopoly but it is now thrown open to the world. Social standing has changed – shifting against them. |

At the beginning of the 19th century the term pitman denoted a craftsman; by the end of the century there had been a gradual devaluation of the pitman’s craft and autonomy so that now miner equated with labourer. This change in attitude can be detected in the occupational names used by enumerators in the subsequent censuses, but whether the substitution of coal miner for pitman was accidental or by choice we cannot tell. We do know that the description pitman does not appear on any census return for either family. It would seem that after the 1840s the term no longer had the cachet previously attached to it.

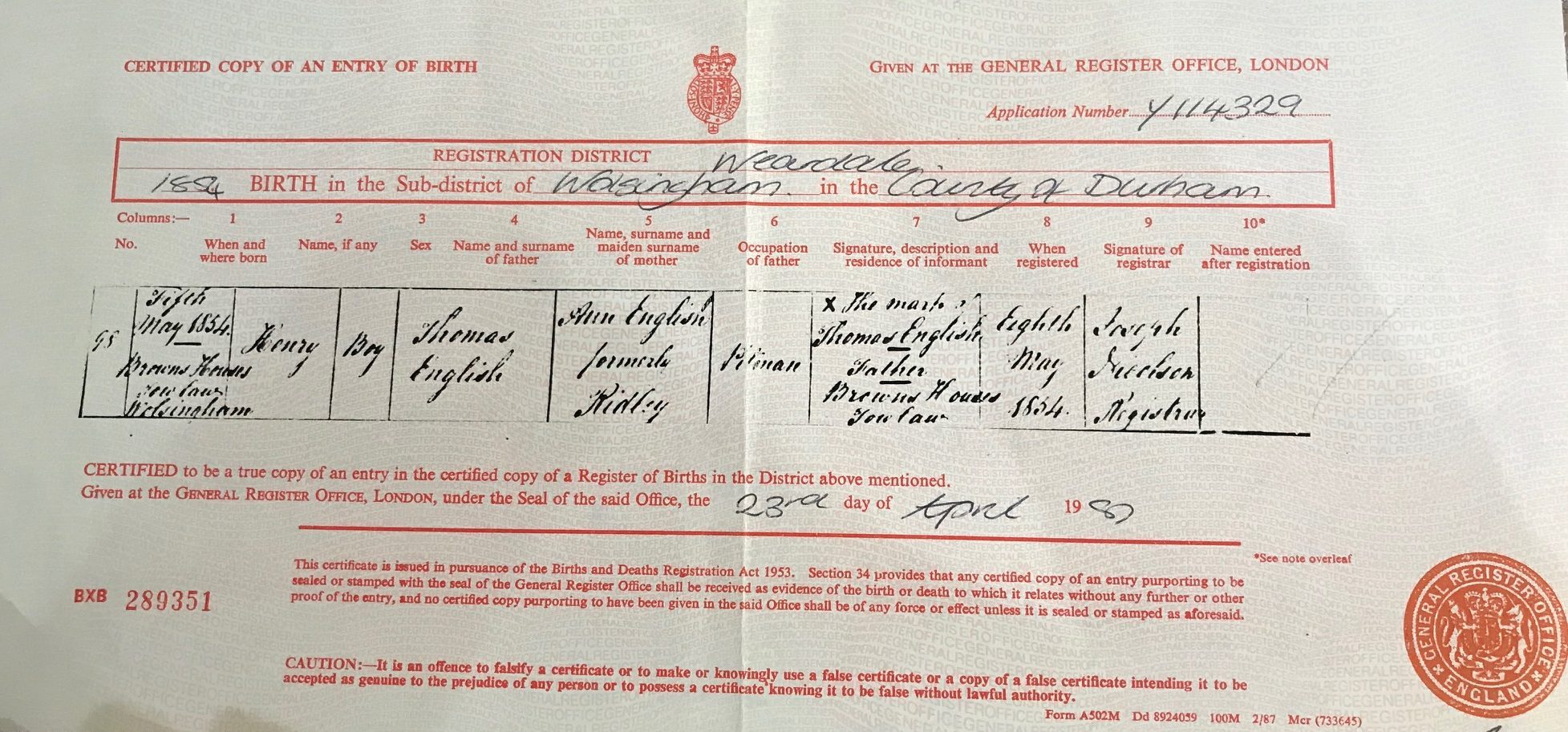

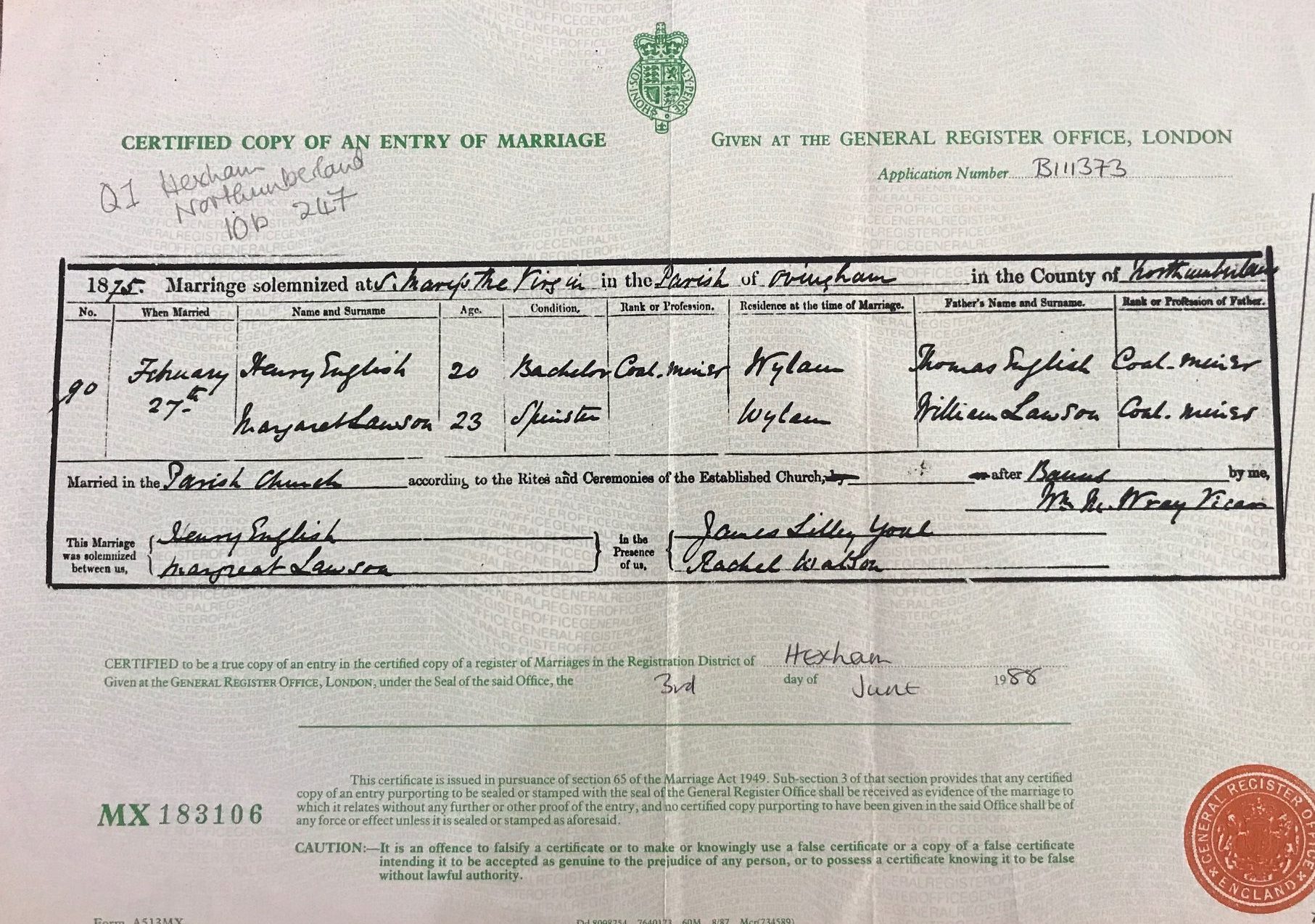

After 1850 (around the time of the birth in 1854 at Tow Law, of Henry, Thomas English’s son and WILLIAM’S father) cottage industries, for example hand spinning using a spinning wheel, or agricultural practices such as hand threshing had become outdated as modern machinery took over. So too in the coalfields. The concept as the pitman as craftsman had been superceded by that of the miner as labourer. Thomas still describes himself as pitman both when he marries Ann Ridley in 1850 and at the birth of his son Henry in 1854 . Henry, however describes himself as a coal miner at his own marriage in 1875 .

This partly began in the 1840s with the development of the northern coalfields, (sometimes referred to as the mushroom collieries) when mine owners such as Lords Londonderry and Lambton used outside labour, often Irish with little or no knowledge of mining safety procedures, to swell the work force or to provide black leg labour during strikes.

The character of the miner as perceived by polite society

Respectable people were warned of the bad behaviour of miners and as a result friendly societies such as Society of Glassmakers of Newcastle stipulated:

| Persons that are infamous, of ill character, quarrelsome or disorderly, shall not be admitted into this society… no Pitmen, Collier, Sinker, or Waterman to be admitted |

This indicated that outside the mines, sinkers were recognized as being different to pitmen and colliers , and all were considered suspect. Miners had a reputation for hard drinking, and fighting too often led to unemployment and the workhouse. They were:

| ……. rough and rowdy people who let their hair down and enjoyed a good fight given any excuse |

Although cock fighting as well as dog fighting and bowling had been banned by Act of Parliament, Hetton was known as the centre for these sports. The police had cracked down on cock fighting, but it still went on with other traditional games such as pitch and toss and quoits, on pay-Saturdays in adjacent fields. Bowling competitions often took place on the public roads attracting hoards of pitmen from different collieries much to the annoyance of travellers.

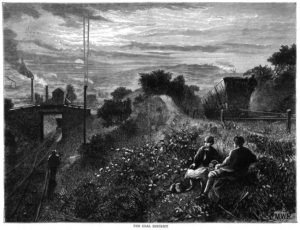

The new coalfields and the railways

Originally mining villages had been part of the rural landscape, but by the 1850s they were increasingly industrial with smoking chimneys and clanking railway lines. Purpose built colliery villages sprang up, solely to accommodate the growing number of miners needed to operate the vast new undertakings. Often they were some way from the original village after which they were named.

Mushroom Collieries was the name given to the new collieries by J Buddle in Evidence to The Royal Commission into Child Labour, 1842, bemoaning the quality of work found in the new collieries from young half-bred pitmen. Craft standards appear to have been waning.

Exploitation of the East Durham coalfield went into full gear after the establishment of rail links in 1829, and The British coal industry expanded rapidly during the 1840s and 50s with the further development of the railways.

Transport links between villages were some of the most developed systems in the country. Roads, wagon ways and railways criss-crossed the area and the mid, east and south Durham coalfields in particular sustained high level of local immigration in the 1840s

Working Life

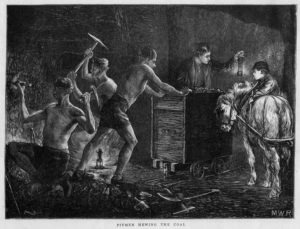

Conditions

During the 1840s there was a general deterioration in the conditions as well as the status of miners.

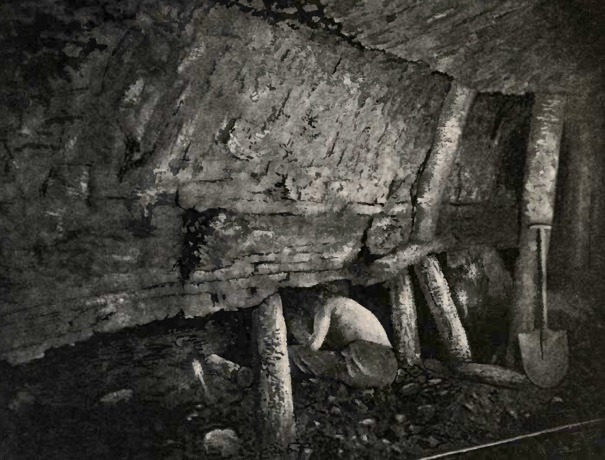

| …begrimed men, kneeling, sitting, stooping, sometimes lying, and hammering at the black wall of coal before them with short, sharp, heavy picks…The pick and the spade are here the hewer’s only weapons; and the intensity of his toil is proportioned to the hardness of the coal and the shallowness of the seam. The best hewers are those who manage, by ingenious shifts of posture, and great endurance, to bring the coal rapidly and freely down… | Imagine a rough, pitch-dark tunnel, three feet wide and four feet high, through which, bent double all the way, and perspiring in a temperature of 75 degrees, you have to shove a wagon holding seven hundredweights of coal. |

| Anon, The Pits and the Pitmen 1850s pp10 -11 | Children’s Employment Commission, 1842 |

Both the above are cited in, The Pitmen of the Northern Coalfields by Robert Colls, 1987.

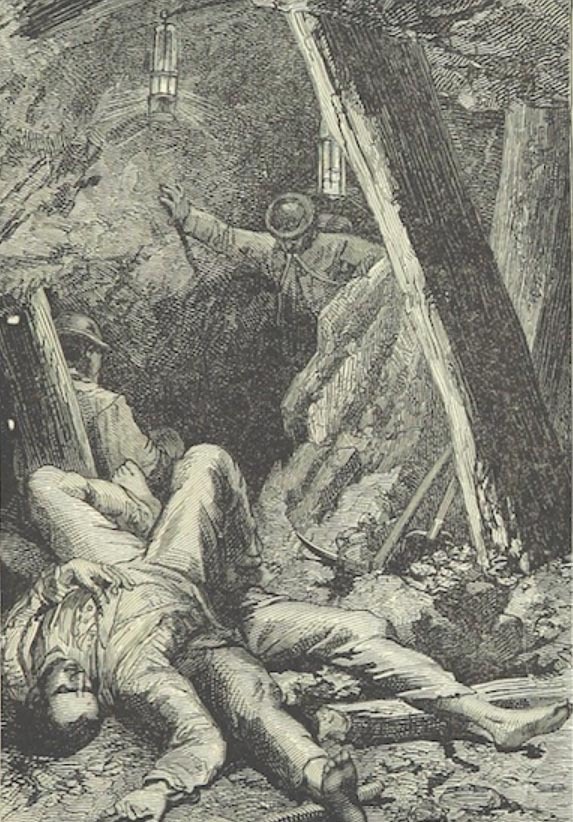

Dangers

The dangers of mining were:

-

-

Increased water and damp

-

Increased gas risk and defective ventilation

-

Increasing incidence of thinner, deeper, hotter seams where men had to work naked and crawl to and fro in the tunnels like beasts of burden

-

The consequence of short-time working where men were pressed to do three days work in two

-

Work with bigger corves (baskets traditionally holding ten to thirty peck and acting as the unit measure of the hewers’ pay). One example was a corve holding 41 pecks – big enough to hold a cow byre at one end and a piggery at the other!

-

Increasing use of gunpowderOwners were reluctant to sink shafts for ventilation – costs

- Types of gas found in Northumberland and Durham pits – fire damp and choke damp

-

Add to this the increased risk to life and limb by digging larger, deeper more dangerous mines and the advent of the Davy Lamp (which enabled owners to mine hitherto abandoned shafts) and a climate of distrust was created of the miners’ ability to work safely. His reputation was undermined.

Lung disease

By 1840s concerns were being raised about what constitutes a ‘comfortable’ current of air at the coalface. Observers noted the respiration of pitmen. The first medical paper looking at black spots on the lungs was published in 1813 but it was not until 1831 that it was related to coal mining. In 1837 in Edinburgh it was established as a disease caused by dust, anthracosis. Later in 1874 it was renamed pneumoconiosis anthracosica. It was still not known whether the condition known as asthma by the pitmen was a chemical or physical condition of gas or dust or both

The Davy Lamp

The Invention of the Davy Lamp made it possible to work in broken, robbed out and collapsing areas. In the 1835 Select Committee, John Buddle (a prominent North East agent) replied to a number of questions including:

Q. Is it your opinion that the loss of life in proportion has been much less since the introduction of the Davey-lamp?

A. No, I think not: but the causes of the loss, and the circumstances of the mines, are perfectly changed; the risk very much increased

Gas accumulated in these idle and buckled workings and, given that their proper ventilation was expensive, Davy provided the excuse not to try. Davy’s invention was often called a murder lamp by the miners. It heightened the dangers by making the broken workings more accessible.

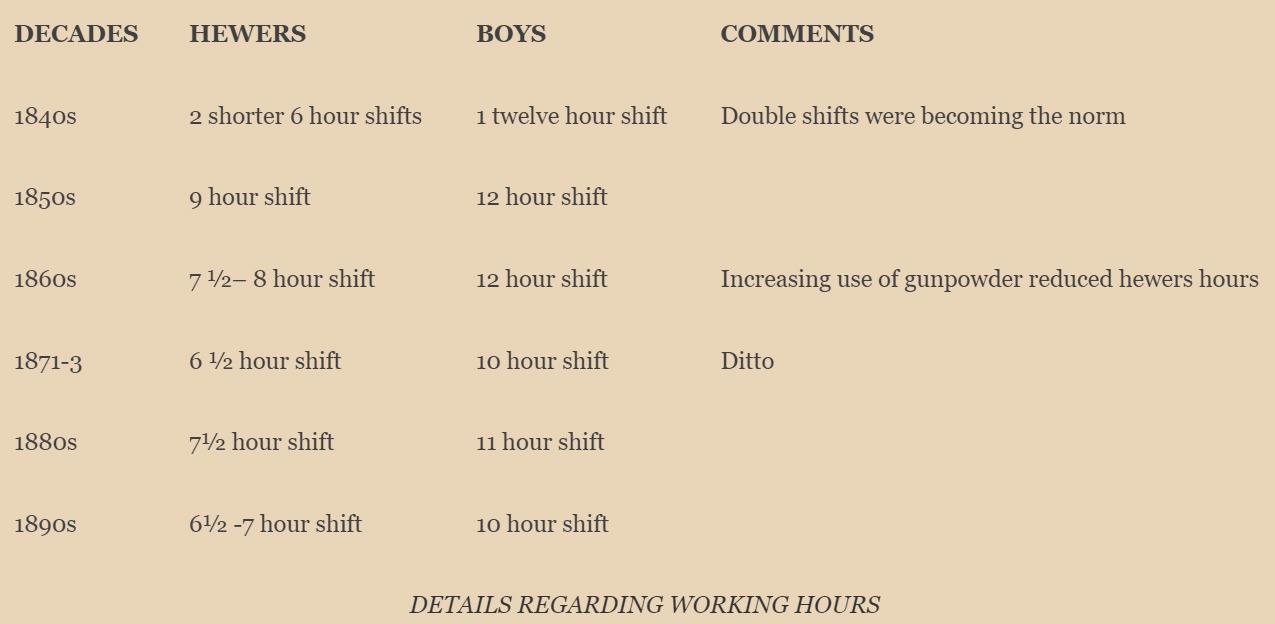

Hours

Until 1842 hewers worked 8 hours and boys 12 hours, although prior to 1832 boys worked 14 hours. It is difficult to establish exact working hours for the pitmen. He was unusual in being able to set his own hours and was largely unsupervised. This autonomy was evidence of his status.

The advanced longwall technique (taking all the coal and allowing the wall to fall) meant a more closely supervised work force.

Labour

Populations grew; for example the population of Murton (near Hetton) in 1831 was 98; by 1851 it had risen to 1,387. In 1831 Thornley had a population of 50; by 1851 it had grown to 2,730. As the villages changed in character so the majority of available jobs were tied to the colliery. Women’s employment possibilities were few, apart from domestic service and seasonal agriculture.

There were proportionately more men, and young men in particular, in the mining areas; the relative health of the mining communities meant the expansion of new collieries encouraged men to look further afield for work. Mining families appear to have had more children than comparable occupations.

In Hetton-le-Hole in 1851 the average mean family size for coal miner heads of household was 4.45 (Sill, Michael (1974) Hetton-Le-Hole: the genesis of a coalmining landscape 1770-1860, Page 102). William English had nine children, seven of which were boys; John Lawson had seven children, three boys of which two died in their twenties.

Outside labour was a bone of contention from the 1820s to the 1860s. From the 1840s there was mounting criticism of pitmen’s skills and their ignorance and wilful disregard of safety measures.

The owners importation of labour from outside the coalfields, particularly during the strikes of 1831-2 and 1844, were sited as examples of this, leading to pit explosions; fear of the use of outside labour rather than the bred pitman was not surprising given the number of pit accidents and the reportedly reckless attitude of many of the newcomers.

| ……there are a great number who are reckless, but they are persons who have been introduced into the mines; they are not persons who have been brought up mining under the tuition of their fathers or relatives |

By 1866 Coal Owners were employing agricultural workers and others thrown out of work by new mechanization. Parliamentary witnesses claimed they could quickly gain the necessary skills needed in the mines. In 1873 it was still thought that a year to eighteen months was adequate. It was recognised however that these new immigrant miners were likely to take risks through inexperience.

Knowledge of the mine came from long experience of mines. Boys starting work at ten years old would work for eleven years from trapping to putting before becoming hewers.

| (I am) decidedly of the opinion that if (boys) are not initiated before they are 13 or 14 – much less 16, 17 or 18 – they never will be come colliers. |

Bred pitmen were efficient, knowledgeable and safe ones. Post 1844 an open labour market gradually became the chief determinant of entry into the industry. This was repeated in every part of the New Northern Coalfield. Men employed from a labouring background were considered the dross of society and labelled ‘the wickedest set on the face of the earth’ in statements in the Second Report on Accidents 1842.

The 1866 Select Committee reported, in effect, not one community but two. There was the better type and the lower type of family. The former was conceived…. .as being more prudent, educated, competent, industrious, and well conducted than the latter. In other words the families of the old pitmen and that of the incomers. There is no way we can be certain which category the Lawson or the English families fell into, but although neither Ann Ridley nor Thomas English appeared to sign their names when they married in 1850, by 1881 Thomas was the manager of a coal mine, so presumably was relatively numerate and literate.

Rates of pay

Piece rates were variable:

Hewers were paid by score price i.e. 20 tubs or corves. Putters (who pushed the full tubs away) were paid by score + distance – these were usually adolescent lads pushing singly or in pairs.

Drivers (who drove ponies and carts), were younger boys, paid by the day.

Trappers (who controlled the underground doorways, – the youngest boys) were paid by the day.

| Compared with other counties, the miners in the north west pits were better paid, and sinkers were always paid more than miners. |

WILLIAM uses the word sinking when referring to the work his father does. Sinkers were the elite among the mining community, enjoying both better wages and better accommodation. There is no evidence however to suggest Henry was one. He consistently refers to himself as ‘miner’ whereas many sinkers were known by name and would have referred to themselves as such. It is more likely that Henry was a Sinker’s Labourer or maybe a Stone Sinker (higher up the sinkers hierarchy). WILLIAM refers to sinking in stone which would support this.

| A common phrase was ‘follow the wark’ when a miner had to face the reality of looking for work. Due to the nature of sinking, pit sinkers were on the move much more than ordinary miners. Employers sent agents around the coalfields to recruit/steal workers from each other’ |

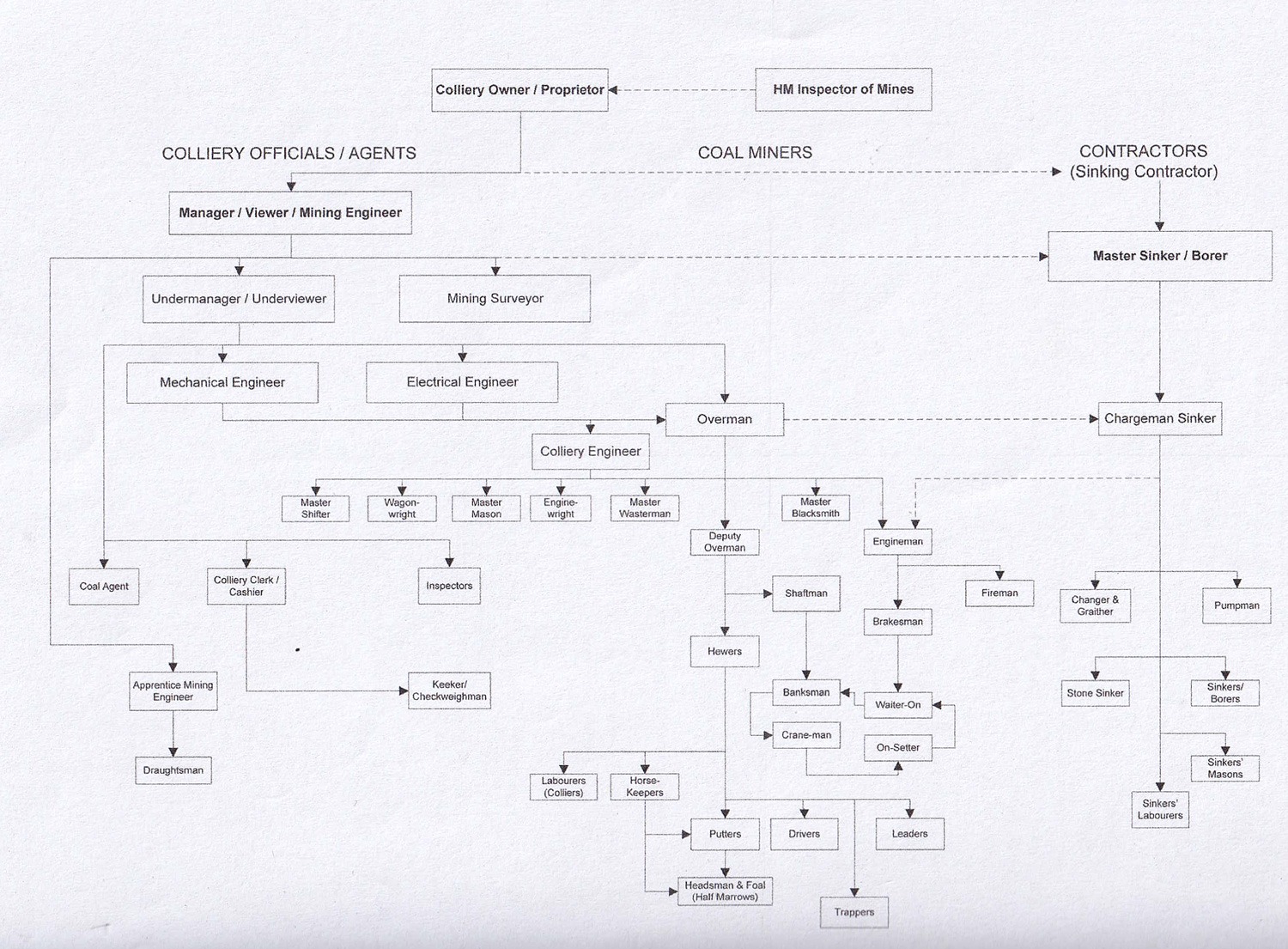

Mining occupations

Mining Occupations from the Durham Mining Museum provides details of the terms used to describe the many occupations in the coalfields.

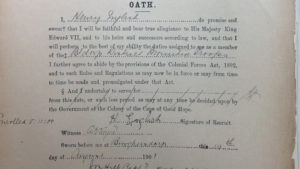

The Bond

There is more information about how the Bond affected the families in Before William’s Birth

The idea of a bond was probably started in the late 17th or early 18th century as an attempt by the coal owners to stabilise the labour force. By 1850s the bond had changed.

The following is item eleven of a typical Bond.

| Each person to whom a dwelling house shall be provided as part payment of his wages, shall keep in good repair the glass in the windows thereof, or pay the said owners for the repairs of the same, it being distinctly understood that the dwelling house provided for any of the persons hereby hired or engaged are to form part of the wages of such persons; and on the expiration of such hiring in case any of them shall quit or be legally discharged from the employment hereby agreed upon, he or they shall at the end of 14 days thereafter quit such dwelling-house or dwelling–houses, and in case of neglect or refusal, such owners shall be at liberty , and he or they, and their agents and servants are hereby authorized and empowered to enter into and upon such dwelling-houses, and remove and turn out of possession such workman or workmen, and all his and their families, furniture, and effects, without having recourse to any legal proceedings’ |

After 1850 the Bond:

• Determined how much a pitman could earn

• Fixed rates of pay for coal extracted

• Set rates of fines for absence or poor work

• Set a mass of allowances and extras by negotiated custom eg the binding day, annual expenses, housing

It became more uniform during 19th century, but rates of pay, fines and allowances tended to vary according to the seam, pit and colliery. Differences in work places were significant.

Rates varied between types of workings, size of coals, distances travelled underground and tub measures.

There was no stability of tenure or even a guarantee of work.

The abolition of the bond in 1872 should have ensured a settled life for the miner of the late 19th century but this certainly was not the case for WILLIAM and his father Henry. The death of his wife Margaret in 1892 seems to have precipitated this need to be on the move and Henry’s restlessness must have affected his son. WILLIAM seems to have been on the move for the rest of his short life.

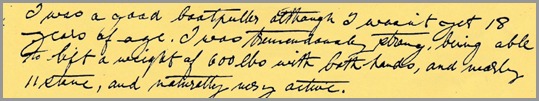

The Big Hewer

Miner’s views

At Merrington Colliery there was:

| A HEWING MATCH EVERY DAY at this flat and in order to satisfy the competition and keep our turn, Bill and I worked like horses, going home after each twelve hour shift with sore and tired bones. This kind of thing, which went on year after year amongst miners, broke down strong men, and kept down the…price in every district. In fact it is only too true that this slavish, ignorant, and clumsy competition kept criminal passions predominant over the better part of the miners nature’ |

In 1844 a Thornley pitman wrote:

| Men and boys do not strive so much for the mastery as they formerly did. He was the best man that could perform the most work and get the largest sum of money. Hewing matches have been frequent, and very often followed up with fighting. These things have been the downfall of Miners for many years but I feel very thankful that the Union and restricting principle …are doing away with these things. |

The Unions views

In order to enforce stricter regulations regarding working hours the United Colliers Union made it a requirement that no hewer was to work more than 8 hours per day nor earn more than 4s 6d. This applied to all 4,000 hewers. If any hewer earned more his entire pay for the day could be forfeited by the Union. This was called RESTRICTION and continued throughout the 19th century. The 1892 Royal Commission on Labour could not break the Union’s defence of it.

Q. There is no exception to your rule; that is to say, that a man, however able and willing to work longer, your association would object to his doing so?

A. Yes

It was most likely an exaggerated claim that some hewers could earn as much as 7 or 8s a day. It is possible, however that a pitman of exceptional strength may have achieved this but it was certainly not the norm at the premier collieries.

The myth

However the myth of the epic big hewer remained a potent source of pitmen’s self identity, best identified in Northumberland and Durham in the figure of John Temperley, a mythically prodigious miner from Craghead. He is a coal legend who appears by a different name in each mining locality (a similar figure with superhuman work powers, John Henry, exists in American work gang mythology). It was claimed he could hew as much coal in 21/2 hours as other men could in 7. Cited in The Pitmen of the Northern Coalfield by Robert Colls (1987) p 32.

The Union frowned on such autonomy.

| It had made a personal cultural conversion towards a collective salvation where ‘we think it fair to stand by each other as a body, and not to go on competing’ |

From the 1820s trade unionism in the coalfields attempted to control the autonomy of the pitman. The culture of the Big Hewer etc….competing with each other for price, was thought to have been the result of this control.

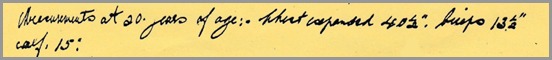

Stories of such prowess would have been relished and handed down with admiration; the cult of the big hewer lived on and it seems certain WILLIAM would have heard such tales. It might go some way to explain his obsession with his strength and physical attributes as outlined in the Journal.

Education

The Royal Commission of 1842 into child labour concluded that children having worked excessive hours in the mines were too exhausted to cope with school work. It was widely accepted that both Religious Instruction and schooling suffered.

Ford Mason reminds us however that most owners and mining engineers supported the view that the coal trade depended on the use of child labour, even if some agreed children would be able to get an education if they started work when older. Unfortunately there were still enough of the old guard who believed that to give any form of education to the lower classes would unsettle them and lead to unachievable aspirations above their station.

| Even John Wesley, founder of Methodism, recommended child labour as a means of preventing youthful idleness and vice |

By the time WILLIAM was of school age it was accepted that children should receive a basic education in the 3Rs. An essential step in the 1840s was the raising of the age of boys to ten years before starting work in mines, to allow children time and energy to start lessons. The education Act of 1870 consolidated this good work by making education compulsory between the ages of 5 and 13.

For many miners Methodism was their first opportunity to get an education. Miners were also urged to attend night school.

Mechanics Institutes, which had started earlier in the 19th century and which were often funded by industrialists such as Robert Stephenson on the grounds they would ultimately benefit from having a more knowledgeable and skilled workforce were also strongly supported by The Chartists and the Trades Unions.

We know WILLIAM attended school

But at present we don’t know where. Before the 1870 Education Act there were Church Day Schools, both Anglican and Methodist, and Methodist Sunday Schools, as well as the National Schools, which since the 1830s had made substantial efforts to put schools into mining districts. There were 26 in 1830s, 64 in the 1840s.

We know one was in Wylam but still have to discover if WILLIAM attended. He was only 7 when the family left the area for Victoria Road, South Shields so it is most likely that that he went to school there. A colliery school had been founded at Whitburn in 1883. Henry was working at Whitburn (Marsden) from 1882 so it is equally possible WILLIAM was educated at the colliery or perhaps at Pegswood after the family moved again.

The Wylam School is mentioned in the Journal.

(At Hetton and Easington Lane the Hetton Coal Company patronized the National School, founded in 1834 so it is possible that WILLIAM’S grandfather Thomas, (b 1828) and his younger brother Ralph (b 1830) might have attended).

Methodism in the coalfield

The Methodists ran Sunday and day schools. An early Methodist magazine contained the following anecdote, obviously a warning directed to miners: ‘Two men ascended a pit shaft, one a Methodist singing hymns, the other a blasphemer singing bawdy songs; the rope surges, the blasphemer falls and is killed, the Methodist is saved; yet again “the Providence of God is illustrated”.’(recorded in The Pit Sinkers of Northumberland & Durham Peter Ford Mason, The History Press 2012)

| The day of darkness is beginning to pass away from the mining districts in the north. The Methodist preachers have been the great pioneers – preparing the way for the illumination of the people’ |

| There are ’few persons of an openly vicious character now, drinking had declined, miners now washed more diligently. |

| A catalogue of vice – dog fighting, cock fighting, gambling, drinking, bowling, swearing, fighting, shamelessness, ignorance and illiteracy- was observed to have fallen into recent and dramatic decline’ |

Methodism was largely credited for these improvements.

Moral improvement

In the 1850s and 60s a Christian ethic of evil and good homes (slovenly and matronly wives) and a state sociology of rough and respectable families (ignorant and educated ones) prevailed.

Weslyan Methodists were credited for having brought a great change in the respectability of dress and general good behaviour of the miners.